Montenegro Turns Blind Eye to Deep-Sea Treasure Hunters

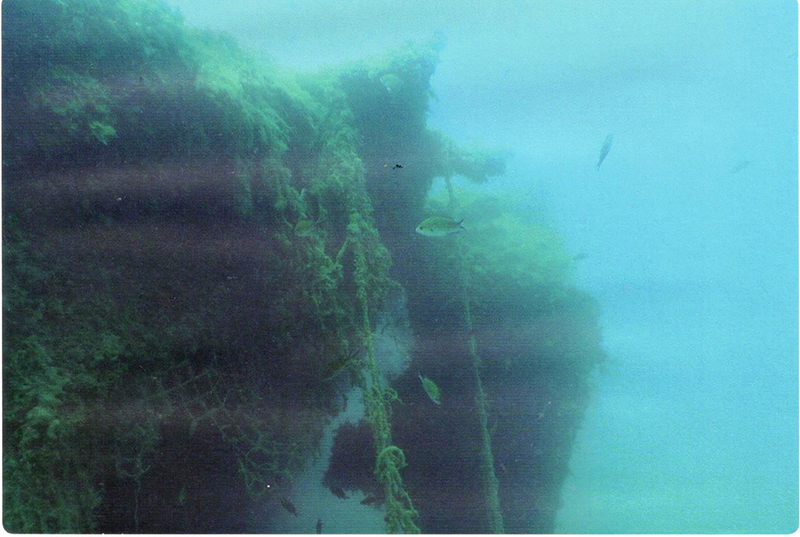

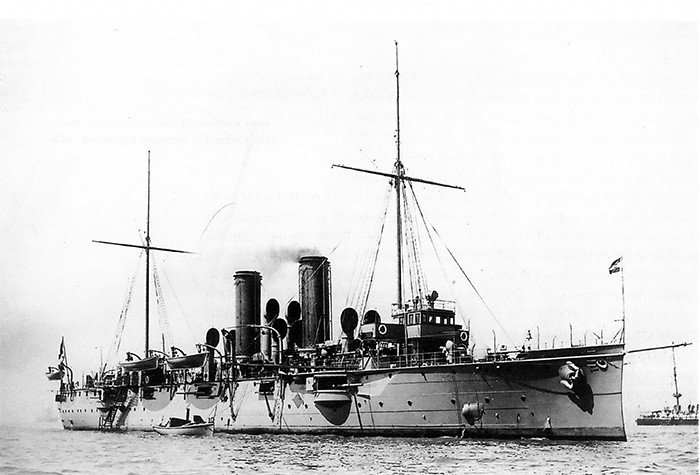

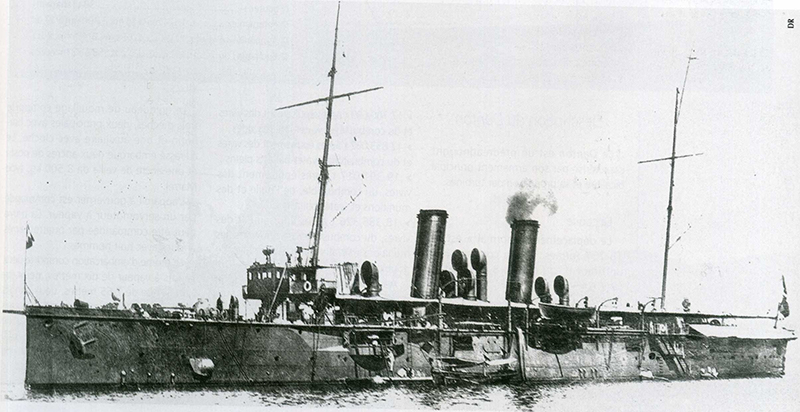

When the Austro-Hungarian cruiser Zenta, the first ship sunk in the First World War, plunged to the bottom of the Adriatic Sea near Petrovac, more than half of the ship’s crew went down with it.

When it set out from the port of Tivat, accompanying the destroyer Ulan on a mission to blockade the Montenegrin port of Bar, the cruiser was already a veteran vessel, pulled out of the reserves. Obsolete, slow and poorly armed, it was an antique among modern ships.

Zenta sank during a battle with the more powerful fleets of France and Britain on August 16, 1914 – and the site of the shipwreck lay undisturbed until divers discovered it in 2001.

Treasure hunters followed soon enough.

Dragan Gacevic, a well-known diver from Herceg Novi and author of the book and documentary TV series Montenegrin Undersea [Podmorje Crne Gore], told CIN-CG/BIRN that thieves soon got to work.

“It is unbelievable that in the meantime someone tried to steal the main compass from the command bridge of the Zenta. That wreck is 73 meters down, and a special gas mixture, the so called trimix, is needed to dive to such depths – which goes to show that these thieves are up for anything,” he said.

“Luckily, they did not manage to remove the compass from the Zenta, but traces of devastation and damage from the thieves’ attempts to remove the entire bowl, and then the core of the compass, are noticeable,” he added.

Gacevic, who spotted the damage in the summer of 2014, said he did not report the case to Montenegro’s Ministry of Culture because the thieves had not succeeded in their intentions.

But an investigation by CIN-CG/BIRN shows that the case of the attempted plunder of the Zenta is anything but isolated.

It shows that the country’s underwater treasures are insufficiently examined, recorded and, most disturbingly, are virtually unprotected.

Although the Montenegrin state has passed laws to protect the country’s cultural goods, it has deployed few staff to enforce their implementation.

As a result, the destruction and theft of the country’s underwater cultural heritage generally goes unpunished.

Most sites at risk also will not enjoy full protection under the current laws until the Ministry of Culture has finished its survey of underwater sites, and has assessed which ones qualify for the status of cultural goods.

However, Montenegro allocates minimal funds for such research. Civil society activists say the Centre for Conservation and Archeology, the body tasked with conducting the research, lacks even the elementary prerequisites to complete the job.

The Centre for Conservation did not respond to CIN-CG/BIRN’s queries about such concerns by the time of publication.

What lies at the bottom of the Adriatic?

Numerous historic sites and treasures lie at the bottom of the sea off Montenegro.

Treasures range from remains of antique structures and Roman and Greek amphorae to medieval ships that sank together with their cargo, and wreckages from the 20th century.

The plunder of these sites started in the second half of the 20th century, but it intensified in the late-1990s, when better diving equipment meant that more people could dive to greater depths.

What started as a couple of individuals taking a few “souvenirs” 60 years ago now has all the markings of large-scale, even organised, robbery.

“It is fairly simple for someone with money to buy some interesting artefacts from undersea poachers, like an antique amphora or an attractive part of a ship’s equipment from some more-than-century-old wreck,” Gacevic observed.

He often dives under the waters and sometimes, between only two or three dives at the same location, notices visible progress in terms of the devastation of the sites.

At the bottom of the Risan Bay, one of the most famous sites, are amphorae, galley dishes, ceramics and glass or bricks dating from the 4th century BC to the 7th century AD.

Many are important evidence of the trading relations of the indigenous Illyrian people, mostly with the Greeks and Romans.

This bay was probably used as a place for short-term anchorage for centuries, as an overnight shelter and as a safe haven from storms, when sailing ships used the interruption to their voyages to lose objects no longer of use in the easiest manner – by throwing them overboard.

This part of the Boka Bay has had protected cultural status for over 40 years, so underwater activities and anchoring are here are strictly forbidden.

Despite that, websites still offer diving tours in the bay. In the summer, anchored super yachts can often be seen there, with their guests swimming in the sea.

(http://www.booking.me/Default.aspx?sifraStranica=1369)

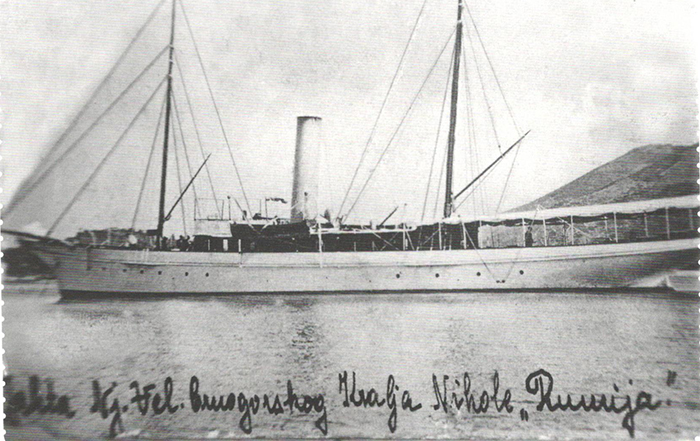

Another case of state negligence, according to Gacevic, is the yacht of Montenegro’s last King, Nikola I, the Rumija.

It sank off Bar in 1915, and did not receive protected cultural good status for exactly a century.

The yacht was a gift to the King from the Ottoman Sultan in 1905, and, apart from meeting the needs of the Montenegrin court, was used in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and during World War I to transport war material.

The wreck of the Rumija is still physically unprotected, however, in the middle of the Port of Bar, only a few meters under water.

That is why, according to Gacevic, it has now been completely destroyed, primarily by anchors and the anchor chains of large trading ships, which sail to the nearby pier for fuel.

Parts and objects have been stripped from the wreck in the meantime, including the ship’s bell, which found its way to a private collection in Novi Sad, Serbia, under unexplained circumstances.

Gacevic himself found it there and identified it and wrote about it in his book, Podmorje Crne Gore, published in 2012 in Herceg Novi.

Another case, about which the country’s Cultural Heritage Inspectorate of the compiled a report in October 2014, which CIN-CG/BIRN has seen, concerns the removal of the propeller from the Austro-Hungarian steamship, Arpad.

This ship was damaged off the coast in 1916 when it hit a mine, but did not sink. However, it did lose its propeller with part of the axis and the steering oar.

The great propeller of the Arpad sank to 48 meters and dug itself into the sandy bottom of the sea.

The three-piece propeller, made of several tons of bronze, disappeared three years ago, which is when unknown persons took it and most probably sold it to collectors of secondary raw materials.

This theft demanded good organisation. Gacevic, who reported the theft to police in September 2014, believes that the heavy propeller could not have been lifted without a crane, a large vessel that hauled it to the shore, a compressor to fill underwater “parachutes” with air, trucks and other logistics.

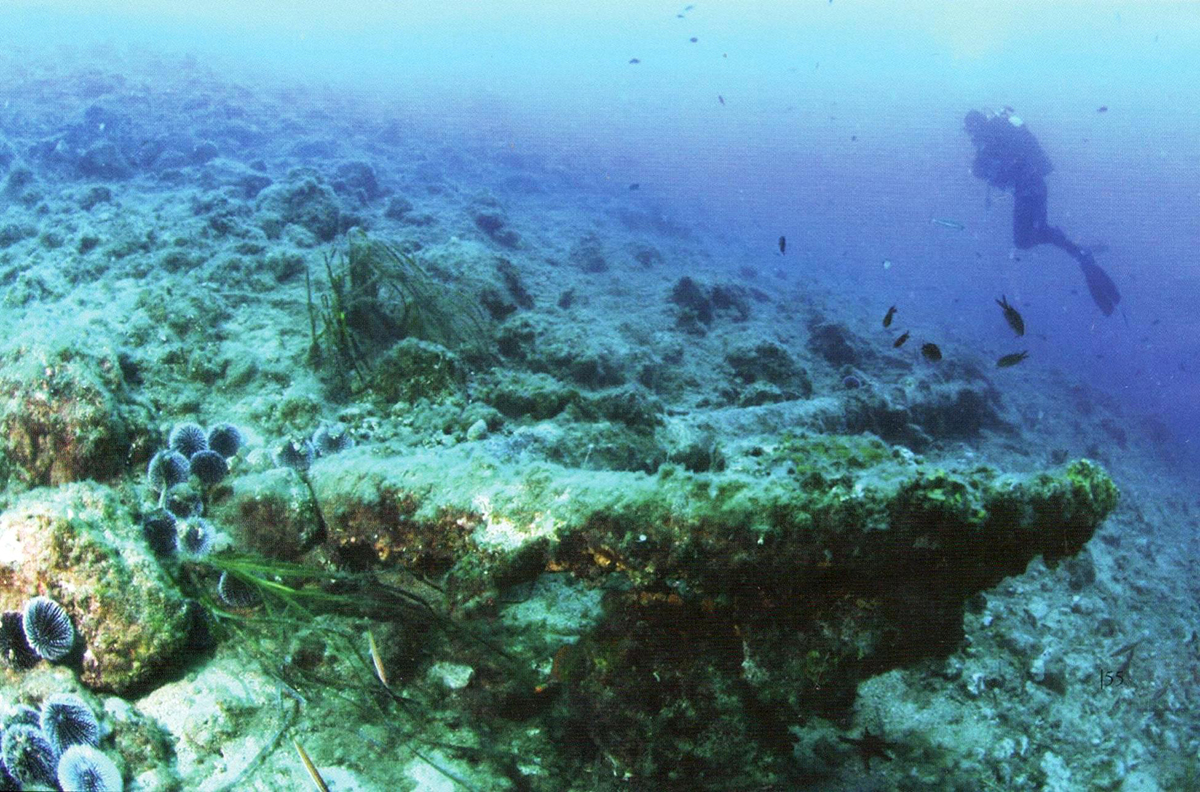

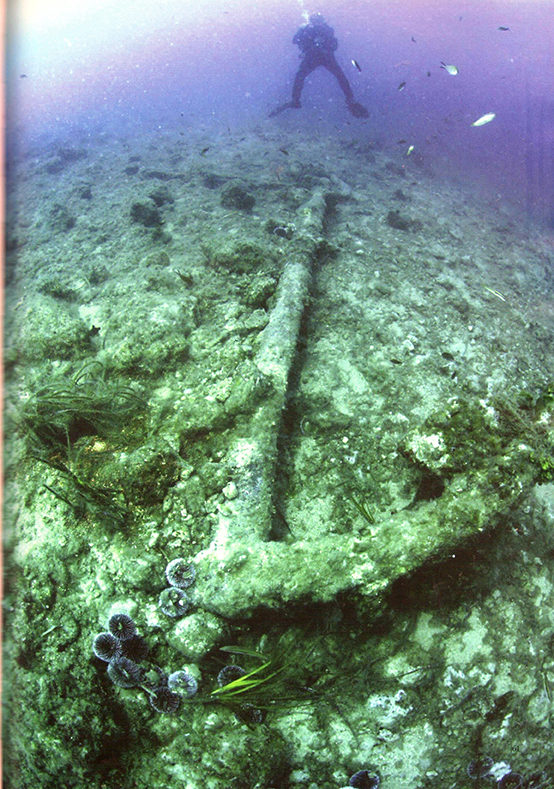

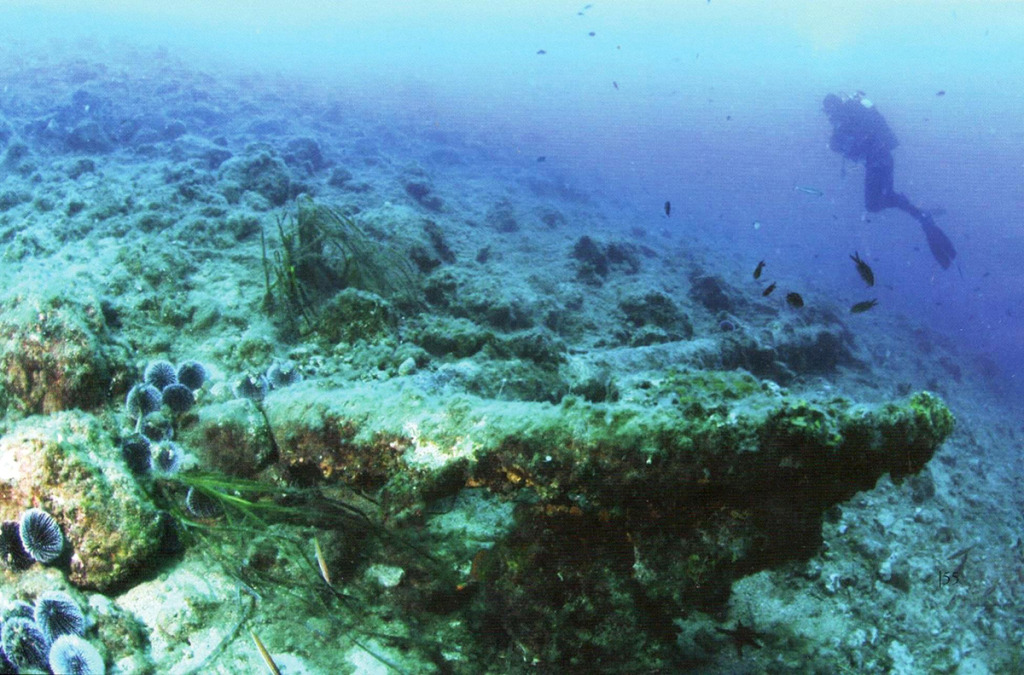

One of the most famous examples of underwater cultural destruction is that of the galleon which sank at Cape Kabala, probably in the 16th century.

It obtained protected cultural good status at the same time as the royal yacht, in 2015.

Of the 35-meter-long ship, with three masts and at least four canons, the seabed has kept the remains of the wooden structure sticking out of the sand, numerous parts of the ship’s equipment – anchors, ship berthing equipment, parts of pumps, an inventory and more.

Gacevic reported the anchor of the galleon missing on September 15, 2014.

That same year, the Ministry of Culture reported this loss to the police, which filed this case as serious theft.

However, the anchor has been exhibited at the entrance to the company Slovenska Alijansa in Herceg Novi for some years.

Only in December 2017 did the Ministry of Culture order the company to return the anchor to its rightful owner – the state of Montenegro.

Last December, two media outlets, Pobjeda and Portal analitika, quoted the report of the Inspection Affairs Department.

This said that a Russian citizen, Aleksandar Belyakov, from Slovenska Alijansa, had stated that the metal anchor had been bought from “unidentified persons” in 2013 when it was “not a cultural good” with the intention to “preserve it, so that it’s not sold for scrap.”

Belyakov did not answer queries from CIN-CG/BIRN, however.

Police Headquarters told CIN-CG/BIRN that the police gave the Prosecutor’s Office photographic documentation about the discovery of the anchor along with statements from four people who had been interrogated.

However, till now, no one has been held accountable for this theft.

“The Basic State Prosecutor’s Office in Herceg Novi, in cooperation with the Police Headquarters, took steps to find the perpetrators of the said crime,” the spokesperson of the Basic State Prosecutor’s Office in Herceg Novi, Nikola Samardzic, said.

Gacevic evaluates the reaction of Montenegro’s institutions to this theft as “a weak and inefficient response of the authorities to evident pillaging.

“It is no wonder that the devastation of historic heritage at the bottom of the sea continues with unabated intensity,” he said.

Hardly anyone to implement the laws

In Montenegro, four locations or objects have the status of protected underwater cultural goods: the Risan Bay, the royal yacht, Rumija, the sunkey galleon near Cape Kabala and the Bigovica Cove.

This latter was used from the 3rd to the 15th century as a winter dock, and numerous antique amphorae, among other things, have been found in its waters.

The Ministry of Culture has noted another 27 underwater archaeological sites, however.

They include several sites where shipwrecks occurred in the 19th and 20th century – noted by the Ministry for what it explained as “the constant degree of danger [to them], though they do not have archaeological potential”.

The country’s laws on culture and the protection of cultural goods, as well as its ratification of the UNESCO Convention on Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, in theory ban all activities in protected cultural heritage sites, except for research and conservation.

Although the other locations do not enjoy such protection, the laws still classify all archaeological material from the ground or water as state property, which no one may appropriate – so that when artefacts go missing from these sites, it should be treated as theft.

Monitoring implementation of these laws is down to the Cultural Heritage Inspectorate, which is part of the Department for the Protection of Cultural Goods in the Ministry of Culture.

However, the Department admits it has few inspectors, adding that efficient protection requires an array of measures.

“It is necessary to systematically empower/strengthen operational legal mechanisms in situ, especially in light of the fact that we have only one or two inspectors,” the Department, headed by Anastazija Miranovic, said.

The Department also calls protection of underwater cultural heritage a “complex issue”, not only for Montenegro but for other countries as well, adding that a variety of problems makes the complete protection of these sites difficult.

Factors that hinder securing underwater sites include “awards of concessions … the geographical positions of the sites, uncontrolled diving activities, fishing, anchoring and dilapidation of sites due to natural processes,” it said.

Decades old Order on Underwater Activities has been in effect in Montenegro. A new Law on Diving, among other things, regulates the award of concessions to diving centres – that is, their rights to take tourists to certain sites under controlled conditions.

On account of a complex situation, the ministry keeps the coordinates of all archaeological shipwreck sites from ancient times to the mid-20th century a secret.

The Culture Ministry, headed by Aleksandar Bogdanovic, said that the department and the authorities under its charge “are taking the necessary measures to prevent illegal underwater activities”.

In October 2016, together with the Maritime Safety Department, the navy and border police – Sector South, the ministry formed a Joint Operational Team to monitor the country’s underwater cultural heritage sites in order to improve controls over them.

“Through the mentioned system, based on the data of the Maritime Safety Department, in the previous period, three cases at one off-shore point were detected, which were not verified as illegal activities,” the ministry said.

“There were no reported and sanctioned perpetrators,” it added to CIN-CG/BIRN.

Police Headquarters also told CIN-CG/BIRN that, although the Joint Operational Team “has been monitoring underwater cultural heritage sites during the summer months, during that time no sites were found to have been compromised”.

Asked about the Risan Bay, where anchored yachts and swimmers are a common sight, Police Headquarters said sites of that level of protected cultural heritage were not under its jurisdiction – although the bay is one of just four sites with top protected status.

“The anchoring of vessels in the Kotor Bay waters is the responsibility of the Harbormaster’s Office of Kotor, so officials of the Border Police – Regional Center of Border Police South, have no authority to control anchored vessels, and also do not have information about the performing of underwater activities at sites of underwater cultural heritage in the acquatorium of the Risan Bay,” Police Headquarters said.

From regulations, to status, to protection

For some of the 27 known underwater archaeological sites in Montenegro to obtain better protection, it is necessary to declare them “cultural goods” for a start.

To obtain such a status, however, the Law on Cultural Goods says an entire set of research and evaluation work must be done to record the details of the sites, assess their value and, finally, decide whether the site deserves such status.

As a first step, the Ministry of Culture started a three-year project in 2017 during which it plans to “implement all the necessary diving prospections, assessments of the condition, character of sites, spatial boundaries of underwater sites with GPS positioning.

“This will create the conditions to start a procedure for establishing protection and establishing the cultural good status of a certain number of sites,” the ministry said.

Research has been done at those sites that have obtained protected status already, to make a complete record of the artefacts, so that these treasures can no longer be taken away without institutions even noticing.

However, this ambitious project has received only modest financial backing from the state.

Although Montenegro increased the total budget for the protection and conservation of cultural goods program for 2018 to 1.1 million euros, it set aside only 14,000 euros for underwater research – 2,000 euros for research around Budva and another 12,000 euros to research the remaining 27 sites that might get cultural good status.

The capacities of the Centre for Preservation and Archaeology of Montenegro, based in Cetinje, are also modest, activists say.

A public institution, formed under an order of the government, it is in charge of the three-year research project in the Risan Bay, among other things.

Archaeologist Milos Petricevic, from the Citizens’ Initiative Bokobran, calls it regrettable that Montenegro has not built up any serious infrastructure for independent underwater archaeological research.

Petricevic says the Cetinje centre “does not have elementary technical prerequisites to efficiently carry out such work, nor does it possess its own diving-technical block with equipment for charging diving bottles, or a portable side scan sonar…”

For now, the centre has the help of Croatia’s International Center for Underwater Research and RPM Nautical Foundation.

The Centre has not responded to CIN-CG/BIRN queries regarding it capacities.

From written to unwritten code

The guidelines of the UNESCO Convention on Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage, which Montenegro ratified in 2008 (http://www.unesco.org/eri/la/convention.asp?KO=13520&language=E&order=alpha), state that only research or conservation activities may be carried out at underwater cultural heritage sites,

The country’s own Law on Protection of Cultural Goods, passed in 2010, meanwhile obliges Montenegro “to provide protection and conservation of all cultural goods located on its territory, including internal waters and territorial sea, as well as to take care of the protection and conservation of the goods located abroad, which are of importance for its history and culture.”

The same law states that “no one is entitled to carry out any activities that may cause damage to cultural goods; damage, devastate or usurp … or appropriate in any other way, hide or market the cultural good of which they are aware, or could be aware, that it was acquired illegally.”

Violations of the provisions of this law incur fines, but not prison sentences, ranging from 400 to 16,000 euros.

Gacevic says the country’s cultural heritage would be better protected already, if only divers respected the unwritten code they should follow underwater.

The code is as follows, he says: “You may leave only the air bubbles the diver breathes out in the sea; you may only photograph the underwater world of wrecks and other sites visited from the sea; you must not kill anything in the sea, except the time that you have at your disposal for diving.”