Životna sredina u Crnoj Gori je brutalno ugrožena i samo posvećene institucije države, koje rade u javnom interesu, i aktivni građani, mogu da doprinesu rješavanju tog problema, saopšteno je tokom današnje promocije publikacije “Stop devastaciji prirode”.

U dvojezičnoj publikaciji je objedinjeno jedanaest istraživačkih tekstova na temu zaštite životne sredine.

“Uništavanje životne sredine će biti zaustavljeno tek kada te institucije budu radile u javnom interesu. Nije dovoljno da institucije donesu dobre zakonske okvire, neophodno su i poštovanje i primjena zakona”, kazala je direktorica Centra za istraživačko novinarstvo (CIN-CG) Milka Tadić Mijović.

Prema njenim riječima, u suštini problema zaštite prirode je “visoka korupcija”.

“Problem zaštite prirode su interesi privilegovane elite i to nije samo slučaj u Crnoj Gori, to je problem i u regionu, to je globalni problem”, rekla je ona.

Publikacija “Stop devastaciji prirode” je objavljena u okviru projekta “Stop 2 READ”, kojeg su, uz CIN-CG, tokom 14 mjeseci realizovali i nedjeljnik “Monitor” i Balkanska istraživačka regionalna mreža (BIRN).

Da korupcija, neefikasna pravna država i interesi privilegovanih pojedinaca stoje iza uništenja prirode u Crnoj Gori i regionu, jedan je od glavnih zaključaka projekta

Novinarka “Monitora” Milena Perović-Korać dodala je i da je Crna Gora u praksi, daleko od ustavne definicije ekološke države. Iako Vlada čini određene napore zakonski okvir u oblasti životne sredine usaglasi sa onim u zemljama EU, država mora da, kako je kazala, učini dodatne napore na harmonizaciji zakonskog okvira.

Da bi se uništavanje prirode zaustavilo, kako je kazala, neophodno je, pored ostalog, kadrovsko jačanje agencija i institucija koje prate stanje biodiverziteta, da donosioci odluka pokažu veću efikasnost u primjeni mjera iz Poglavlja 27 – životna sredina i klimatske promjene. Biće potrebno, kako je rekla, ojačati ulogu obrazovnih institucija, medija i nevladinog sektora, te uspostaviti partnerske odnose sa donosiocima odluka...

Tadić Mijović je uvjerena da uništenja prirode mogu da zaustave i građani i dodaje da o tome najbolje svjedoče nedavna dešavanja na Žabljaku, gdje su se mještani pobunili zbog sječe drveća u Nacionalnom parku “Durmitor” i plana Vlade da dozvoli privatnom investitoru gradnju usred na samoj obali Crnog jezera. Da aktivni građani mogu da sačuvaju životnu sredinu, kako je kazala, pokazali su i građani Bara, koji su se mjesecima borili da zaustave planove za izgradnju vrtića u dvorištu Gimnazije “Niko Rolović”, gdje je, zbog tog plana, posječeno i preko 90 čempresa starih skoro vijek.

“Dužnost je svakog pojedinca, građanina da štiti prostor, da štini ono što bi trebalo da ostavimo generacijama poslije nas”, rekla je ona.

Iz CIN-CG, BIRN-a i Monitora su najavili mogućnost nastavka projekta, koji bi u tom slučaju bio proširen i na region, te pozvali novinare da iskoriste mogućnost dodane edukacije i rada sa najboljim mentorima koje u ovom trenutku Crna Gora može da im ponudi.

Tadić-Mijović je podsjetila da je učešće u projektu bilo otvoreno za sve crnogorske novinare.

“Zadovoljstvo mi je da smo u ovom izuzetno podijeljenom medijskom prostoru uspjeli da okupimo novinare iz drugih redakcija, poput RTCG, te portala Ulcinj-info”, kazala je ona.

Dodala je i da je obaveza medija da izvještavaju o temama od javnog interesa, te da mediji, uz civilni sektor, mogu da naprave dodatne pritiske na donosioce odluka i alarmiraju javnost.

“Ove teme su zanemarene, ali su jako važne”, poručeno je sa promocije publikacije “Stop devastaciji prirode”.

Konferencija Proces evropskih integracija, sloboda medija i poglavlje 27, održaće se 22. marta u organizaciji Centra za istraživačko novinarstvo Crne Gore (CIN-CG). Događaj će otvoriti Aivo Orav, šef Delegacije Evropske unije u Crnoj Gori, a više domaćih i inostranih stručnjaka, civilnih aktivista i novinara govriće o značaju slobode medija za proces evropskih integracija, posebno poglavlje 27. Na kraju skupa formulisaće se zaključci i preporuke.

Konferencija se organizuje u sklopu projekta: Medijska istraživanja – Stop 2 READ (regionalnim ekološkim aktima devastacije), koji sprovodi CIN-CG u partnerstvu sa Balkanskom istraživačkom regionalnom mrežom (BIRN) i nedjeljnikom Monitor. Projekat, koji se završava u aprilu, je podržan od strane Delegacije Evropske unije u Crnoj Gori i kofinansiran od Ministarstva javne uprave Vlade Crne Gore. U okviru projekta objavljen je značajan broj istraživačkih priča koje su se bavile pitanjima ekologije i održivog razvoja. U istraživanjima su učestvovali novinari iz više redakcija iz Crne Gore.

Konferencija će se održati u hotelu Centre Ville i biće otvorena za medije.

The medieval fortified town of Kotor in Montenegro risks losing UNESCO world heritage site ranking as the rivers of tourists gush out of cruise ships and flow through the gates of the old town. Environmentalists and experts sound alarm bells for the Bay of Kotor’s delicate ecosystem.

Dusan Varda recalls strolling through the old town of Kotor one late autumn evening last year. “There was almost no one out except impeccably dressed waiters in empty luxurious restaurants – that was common perception of Kotor in off-season,” he said, lamenting the new outfit of the old walled city and its Venetian palaces nestled in the Bay of Kotor, a unique fjord in this part of Europe. “I feel nostalgia for the old days Kotor, of 5, 10, 20 years ago,” Varda said.

Kotor appears abandoned in off-season. However everything braces up for the spring and the summer when the cruise ships arrive, disgorging thousands of tourists. Each tourist spends on average €40 per day.

Mr Varda is director of the Mediterranean Centre for Environmental Monitoring (MedCEM) based in Montenegro’s port city of Bar. He is concerned with the environmental situation in the bay. It’s not just tourists who disembark from the cruise ships.

Even though Kotor’s treasury is filled up with new revenues the environmentalists and field experts say that the authorities are blind to the side effects – noise, air and sea pollution.

Kotor ranks third in the Mediterranean when it comes to cruise ship visits. Only Venice and Dubrovnik are ahead of it. However, such influx of tourists drove out the local residents.

In the interviews for Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Centre for Investigative Journalism of Montenegro (CIN-CG) the concerned called upon authorities to urgently assess the environmental impact of cruise ships and regulate their traffic in the Bay of Kotor by restricting access to certain areas.

Western countries “realised their mistakes in tourism industry long time ago” and banned cruise ships from entering the protected areas, said Varda.

As something to start with, he said, Kotor should follow Dubrovnik’s example. The authorities introduced quotas on cruise ships docking there.

“The problem in Montenegro is so called ad hoc tourism” he told BIRN & CIN-CG. “We cannot afford to sit and await the total collapse of natural and human resources in the area before taking action and imposing restrictions”.

Monitoring is “insufficient”

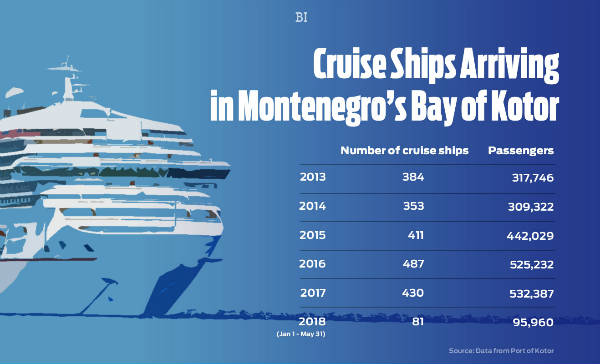

Over the past five years, roughly 2,000 visits of cruise ships brought more than two million tourists to Kotor’s medieval walls and ramparts.

Cruise-ship tourism accounts to some 2% of global tourism industry. Nonetheless, it has become far more important in Montenegro. In 2007, cruise ships accounted to 4% of tourism which quickly rose to 29% in 2016.

Nevertheless, the impact of those floating hotels, mega yachts and sailing boats on the Bay of Kotor (colloquially- Bocca) has never been properly studied- say experts of Kotor-based Institute of Marine Biology (IMB).

Vesna Macic, a senior scientific associate at the Institute, told BIRN & CIN-CG that the monitoring carried out by Montenegro’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was “insufficient”. EPA replied BIRN & CIN-CG inquiry saying that “potential points of tension have been identified but no further analyses has been done”. The agency’s 2016 environmental report cited “possible sea pollution by waste water, solid waste, air pollution (primarily by acidifying agents) and noise”. Cruise ships were listed among greatest threats due to enormous loads of fuel which could wreak havoc in case of accident. While the traffic is on the rise so is the danger of accidents.

The Port of Kotor reports that at times up to three cruise ships are docked in the port staying up to 12 hours each. The Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism (MORT) and the Regional Action Centre for Specially Protected Areas (RAC/SPA) commissioned a study on marine biodiversity of the area in 2014. The study considers the cruise ships in the Bay of Kotor a threat to its biodiversity. “Huge cruise ships in the bay affect fishing as they cut and destroy the fishing nets on their trajectories.The marine life is also at risk because of cleaning agents and waste water discharged from the ships” the study says. The study recommends further regulation of cruise ships in the bay and the zones of restriction where no ship anchoring is allowed.

Furthermore, they pose a threat to seabeds of flowering sea grass (Posidonia oceanica) and protected sea grass species such as Cymodocea nodosa which absorbs carbon dioxide.

Dobrota, a residential area on the city’s outskirts, is recognised in the study as the only place in the bay with colonies of flowering sea grass and is home to Pinna nobilis, commonly known as the noble pen shell which is highly sensitive to pollution.

Noise and air pollution

It is not only the sea that is at risk. Ross Klein, a Canada-based professor and cruise industry expert, says that one docking of a cruise ship releases more pollutants into the air than 2,000 cars and lorries in the whole year.

Marine mammals are especially vulnerable. ASCOBANS, an organisation involved in protection of small whales in the Baltics, the NE Atlantic, the Irish Sea and the North Sea, concluded in 2009 that low-frequency noise in the sea doubles every ten years, starting from 1950. Hearing is primary sense for orientation and communication of mammals.

A study in Croatia found out that some species of dolphin, disturbed by the noise of ships, spend less and less time in search for food and partners thus becoming more recluse. A similar study “should be commissioned for the Bay of Kotor asap,” said Macic, “because the underwater noise has intensified and become more frequent”.

Organic, non-organic and solid waste discharged from cruise ships is another problem.

The US Environmental Agency estimates that each passenger produces from 2.6 to 3.5 kg of waste every day. The waste stored on cruise ships contains a hazardous mix of cleaning agents, paint and medical waste. Its discharge is prohibited in the Mediterranean within 15 nautical miles from the shore. Nevertheless experts warn about difficult enforcement of the regulation. The problem becomes worse in the summer months when the sea temperatures are high, winds are low and water circulation slows down. Furthermore the coastal populations grow exponentially.

Invasive species

Ballast water is seen as another threat to marine ecosystems. In 2013, the Geneva-based International Maritime Organisation (IMO) recognised the impact of ballast water used by big ships to maintain stability, as an environmental threat on the global level. Biologists warn that a cubic meter of ballast water sucked in one port and discharged in another – may contain up to 10,000 sea organisms.

A study made in 2006 in neighbouring Croatia found out that around 2.5 million tons of ballast water were discharged into the sea, introducing 113 new species of sea organisms into the local ecosystem. Certain invasive species multiply without control, suppressing and destroying the autochthonous species. In Croatia, the intruders include the red algae, which is particularly harmful to the Adriatic's biodiversity.

No assessment of the impact of ballast water has ever been done in Montenegro.The Environmental Protection Agency said it expected new analyses about the ballast water in Montenegro’s part of the Adriatic.

UNESCO has warned that “a large number” of cruise and freight ships in the Kotor area is putting at risk the city’s credentials as a world heritage site. The site covers not just the medieval town but the nature and landscapes around too.

“It’s not possible to maintain a balance between mass tourism and environmental protection” said Varda.“One must subjugate the other. Unfortunately, there is a growing fascination with mass tourism and growing [tourism] figures in Montenegro, while nobody mentions the long-term quality and sustainability of the said tourism.”

(Un)protected marine areas

Montenegro is one of a few Mediterranean countries without a single protected marine area. Chapter 27 of the European Union accession talks mandates the existence of at least one.

“For decades, protected marine areas have been recognised across the world as the most efficient way to preserve the marine ecosystems“ Varda said. EPA says it plans to establish one protected zone through a project launched last year worth almost $1.8 million. “Preparations are under way for almost a decade” said Varda.

“Given the current planning, in less than three years we hope to have the first marine protected area established in the vicinity of Katic, an island off the shore of Petrovac, from Platamuni towards the Bay of Traste, in the areas of Ratac and Zukotrlica, Stari Ulcinj and Valdanos”.

Floating palace

The largest cruise ships that have docked in the Bay of Kotor are the Majestic Princess and the Royal Princess, each 330 metres long and accommodating 3,500 passengers and 1,500 crew members.

The Port of Kotor records visits throughout the year, not only in the summer months. The cruise ships Regina della Pace, Artemis and Athens traditionally open cruising season in the Bay of Kotor in early January, and close it on or around New Year’s Eve.

Few complaints

Despite heavy traffic in the bay, only four complaints have been lodged to the Maritime Safety Authority in regard to cruise ships in the Bay of Kotor. The objections are related to pollution.

BIRN & CIN-CG tried to find out from the authorities if any cruise ship has ever faced sanctions during its stay in the bay and the grounds thereof. The Port of Kotor, the Safety and Security Inspection of Kotor and the Ministry of Transport and Maritime Affairs simply ignored our inquiry.

Matija OTAŠEVIĆ

Turistička organizacija ima računicu prema kojoj svaki gost sa kruzera ostavi 40 eura. Agencija za zaštitnu životne sredine, instituti i resorna ministarstva za sada ne prave analize kolika je ekološka šteta u zalivu u kome se vodena masa promijeni samo jednom u sto godina.

„Žalim za Kotorom od prije pet, 10 ili 20 godina. Krajem jeseni sam šetao uveče Starim gradom u kome gotovo da nije bilo nikoga osim upeglanih konobara u praznim, sada uglavnom luksuznim restoranima – što je slika koja postaje uobičajena za Kotor van sezone.“

Dušan Varda, režiser i predsjednik Upravnog odbora barskog Mediteranskog centra za ekološki monitoring (MedCEM), ovako opisuje drevni grad u kojem je, kako kaže, sada sve prilagođeno kruzing turizmu.

Kotor se našao na trećem mjestu na Mediteranu po posjeti kruzera – ispred njega su samo Venecija i Dubrovnik. Prihodi od te turističke grane čine značajan dio prihoda opštine. Preciznih podataka nema, ali procjena lokalne Turističke organizacije je da gost sa kruzera u Kotoru prosječno potroši 40 eura.

Vlasti, kako se čini, izgleda vide dalje od profita i ne žele da se bave drugom stranom medalje, uticajem kruzera na osjetljivu biosferu Kotorskog zaliva - zaključak je istraživanja Beogradske istraživačke mreže (BIRN) i Centra za istraživačko novinarstvo Crne Gore (CIN-CG).

Stručnjaci i aktivisti za zaštitu životne sredine, u razgovoru za BIRN/CIN-CG ocjenjuju da će Crna Gora morati što prije da izradi studije i procjene uticaja kruzera na životnu sredinu, dodatno reguliše njihovo prisustvo u Boki Kotorskoj i odredi djelove u kojima je zabranjeno sidrenje, kako bi sačuvala zalivski živi svijet.

Evropski eksperti preporučuju da se u zalivu odrede zone u kojima bi svaka ljudska aktivnost trebalo da bude najstrože zabranjena.

Razvijene zemlje su, objašnjava Varda za BIRN/CIN-CG,, odavno uvidjele greške u turizmu, te su kruzeri protjerani iz gotovo svih zaštićenih područja u moru (MPA – Marine Protected Areas).

„U slučaju Kotora, prvi uslov bi bio da se ograniči broj dozvola za uplovljavanje i posjeta kruzera. To su uradili u Dubrovniku, mislim da je realno da se takva odluka uskoro donese i u Crnoj Gori.

Nije neophodno da se desi opšti kolaps prirodnih i gradskih kapaciteta da bi neko zaključio da se moraju uvesti ograničenja. Problem u Crnoj Gori je što se turizam uglavnom razvija stihijski“, zaključuje on.

[youtube v="IzOX6LETa54"]

Veliki broj brodova - ogroman pritisak na zaliv

Sa oko dvije hiljade kruzera koji su u prethodnih pet godina uplovili u Kotor, unutar gradskih zidina slilo se više od dva miliona putnika. I dok prema procjenama iz studije Hrvoja Carića i Pitera Makelvorta, („Uticaj kruzing turizma na životnu sredinu – Pogled sa Jadranskog mora”, 2014) udio kruzing turizma u svijetu ne prelazi dva odsto ukupne turističke industrije, podaci Agencije za zaštitu životne sredine, govore da se to u Crnoj Gori kreće uglavnom uzlaznom putanjom, od četiri odsto u 2007. do 29 odsto u 2016. godini.

Pritisci kruzing i jahting turizma na živi svijet Bokokotorskog zaliva nijesu valjano analizirani, potvrđeno nam je iz kotorskog Instituta za biologiju mora. Prema riječima višeg naučnog saradnika ove ustanove dr. Vesne Mačić, „monitoring koji sprovodi Agencija za zaštitu životne sredine nije dovoljan“.

Na pitanje BIRN/CIN-CG, da li je Agencija za zaštitu životne sredine do sada radila analize različitih pritisaka, prije svega kruzing turizma na biodiverzitet Kotorskog zaliva, iz ove ustanove odgovorili su da su „konstatovani potencijalni pritisci, ali da detaljnije analize nijesu rađene“.

Moguće probleme za okolinu ova Agencija obradila je u „Informaciji o stanju životne sredine za 2016. godinu“, ali tek kroz uopštenu ocjenu da su „moguća zagađenja mora otpadnim vodama, čvrstim otpadom, zagađenjem vazduha (primarno zakiseljavajućim materijama) i bukom“. Kao najveće potencijalne prijetnje za zaliv izdvojili su moguće „havarije broda, što bi moglo imati šire posljedice s obzirom na velike količine goriva koje takvi brodovi sadrže“.

Posebno opterećenje dešava se kada je više kruzera istovremeno usidreno. Prema podacima Luke Kotor, u više navrata su istovremeno bila su usidrena čak tri kruzera, koja tu u prosjeku borave oko 12 sati. I dok nadležni počinju da se pitaju na koji način prisustvo velikog broja kruzera u malom zalivu utiče na živi svijet, kao početna tačka za istraživanje tih uticaja može poslužiti studija o morskom biodiverzitetu na području Kotorsko-Risanskog zaliva iz 2014. godine.

Ona je realizovana u saradnji Ministarstva održivog razvoja i turizma (MORT) i Regionalnog akcionog centra za posebna zaštićena područja i zaštitu biodiverziteta Mediterana (RAC/SPA), i u njoj se navodi da prisustvo kruzera u Zalivu predstavlja ogromnu opasnost.

U studiji je primijećeno da su brodovi najčešće usidreni u istočnom dijelu zaliva, u neposrednoj blizini Kotora, te da „prisustvo ogromnih kruzera u zalivu ima uticaj kako na mali ribolov, jer sijeku i uništavaju ribarske mreže duž svoje rute, tako i na morsko okruženje zbog čišćenja plovila i ispuštanja otpadnih voda“. Preporuka eksperata je jasna: dodatno regulisati prisustvo kruzera u zalivu i odrediti dijelove u kojima je zabranjeno sidrenje.

Regulisanjem sidrenja u Kotorskom zalivu zaštitile bi se neprocjenjivo važne livade morske cvjetnice (Posidonia oceanica) i takođe zaštićene morske trave latinskog naziva Cymodocea nodosa. I dok je, prema riječima dr. Mačić, morska cvjetnica, koja je svjetskim i evropskim zakonima zaštićena kao prioritetno stanište Mediterana i najveći proizvođač za more dragocjenog ugljendioksida, u djelimičnoj, Cymodocea nodosa je u velikoj regresiji.

Značaj ovih livada prepoznat je i u pomenutom RAC/SPA izvještaju. Dobrota je tom studijom prepoznata kao jedina tačka u zalivu sa kolonijama morske cvjetnice, ali i sada skoro istrijebljene školjke periske (Pinna nobilis), dok Verige igraju izuzetno važnu ulogu u spajanju Kotorskog zaliva sa ostatkom Boke i otvorenim morem, a imaju i veoma bogatu floru na dnu. Ovo su, prema preporukama evropskih stručnjaka, zone u kojima bi svaka ljudska aktivnost trebalo da bude najstrože zabranjena.

Zagađenje gore od kolone kamiona

Zagađenje vazduha nije ništa manja opasnost po ekologiju država koje privlače veliki broj kruzera. Naučnik Ross Klain koji proučava kruzing turizam, procjenjuje da se samo jednim pristajanjem kruzera u luku u vazduh emituje više zagađenja nego što to učine dvije hiljade automobila i kamiona za cijelu godinu.

Posebno su ugroženi morski sisari. Organizacija koja se bavi zaštitom malih kitova u Baltičkom moru, sjeveroistočnom Atlantiku, Irskom moru i Sjevernom moru (ASCOBANS) 2009. godine, kako navode Carić i Makelvort, zaključila je da se niskofrekventna buka u moru od 1950. u narednih šest decenija svake dekade dvostruko povećavala. Buka posebno negativan uticaj ima na morske životinje kojima je sluh primarno čulo za orjentaciju i komunikaciju.

Studija manjeg obima, izrađena u Hrvatskoj, pokazala je da pojedine vrste delfina, frustrirane bukom koju proizvode brodovi, sve manje vremena provode u potrazi za hranom i pareći se, dok se sve više osamljuju i izbjegavaju bilo kakav kontakt.

Takvu analizu bi, apeluje Mačić, „što prije trebalo raditi u Kotorskom zalivu zato što je podvodna buka postala vrlo intenzivna i frekventna“. Iako priznaje da za to nema čvrste dokaze, Mačić kaže da je iz razgovora sa stručnjacima koji proučavaju morske kornjače, a „znajući situaciju u zalivu“, zaključila „da su slučajevi kada su ove vrste 'napadale' plivače izazvane djelimično, ako ne i prije svega, zbog velike buke pod morem i gužve na samoj površini“.

Problem koji u ovim studijama nije na adekvatan način obrađen, a izuzetno je značajan, jeste emisija organskog, neorganskog i čvrstog otpada sa kruzera. Mačić vjeruje kako je teško utvrditi da li je neki otpad u more dospio sa kruzera ili sa obale. Američka Agencija za zaštitu životne sredine još ranije je ukazala na alarmantan podatak – procijenjena količina proizvodnje otpada na kruzerima dnevno je između 2,6 i 3,5 kilograma po osobi.

Problematično je i to što otpad skladišten na kruzerima sadrži i opasnu smješu sredstava za čišćenje, boje i medicinskog otpada. Organski otpad na Mediteranu je strogo zabranjeno ispuštati u području od 15 nautičkih milja od obale ali to je izuzetno teško kontrolisati konstatuju Carić i Mackelworth u pomenutoj studiji.

Dodatni problem tokom ljetnjih mjeseci u Bokokotorskom zalivu, predstavljaju i visoka temperatura mora, vrijeme bez vjetra i cirkulacije vode, te višestruko povećanje količine organskog otpada usljed prosječno tri do pet puta povećanog broja stanovnika uz obalu. Tome, navodi se u izvještaju Agencije za zaštitu životne sredine za 2009. godinu, ide u prilog i činjenica da je za zamjenu cjelokupne količine vodene mase u Bokokotorskom zalivu potrebno čak 100 godina.

Kada se razmišlja o rješavanju problema otpada u Zalivu, treba imati u vidu i podatak da čak i Dubrovnik, kao jedna od najrazvijenijih luka za prijem kruzera na Jadranu, kako konstatuju Carić i Makelvort, ima veoma nerazvijen sistem i slab monitoring emisije štetnih materija sa kruzera.

Balastne vode donose nove stanovnike

Međunarodna pomorska organizacija (IMO) iz Ženeve je 2013. godine prepoznala da takozvane balastne vode predstavljaju jedan od najvećih ekoloških rizika u svijetu. Veliki brodovi poput teretnih i kruzera, koriste ove vode kako bi osigurali stabilnost i upravljivost tokom plovidbe. Uzimaju se najčešće u jednoj luci, a ispuštaju u sljedećoj. Prema procjenama biologa, kubni metar balastnih voda može sadržati i do deset hiljada morskih organizama.

Iako je negativan uticaj balastnih voda na morski ekosistem prepoznat kao realan, ne postoje studije koje detaljnije obrađuju ovaj problem. Procjena uticaja nema ni u Crnoj Gori.

U Hrvatskoj je, međutim, 2006. godine urađena analiza koja je pokazala da je oko dva i po miliona tona balastnih voda ispušteno u more, pri čemu je u ekosistem uvedeno 113 vrsta morskih organizama, od kojih 61 do tada nije bila prisutna, dok su 52 proširile svoje stanište zbog klimatskih promjena.

Najveći broj destruktivnih vrsta, kako se ističe u studiji Carića i Makelvorta, koje ugrožavaju domaće organizme, u hrvatski dio Jadranskog mora donijeli su brodovi kroz balastne vode. Posebno opasna po biodiverzitet Jadrana je invazivna crvena alga (Womersleylla setacea). Invazivne vrste, naime, zbog nedostatka prirodnih neprijatelja počinju nekontrolisano da se razmnožavaju na novom području, i tako suzbijaju i uništavaju autohtone vrste u tom staništu.

„Nemoguće je napraviti balans između masovnog turizma i zaštite prirode. Jedno se mora podrediti drugome. Nažalost, u Crnoj Gori vlada fascinacija masovnim turizmom i brojkama koje rastu, a niko ne priča o kvalitetu i održivosti turizma na duge staze“, primjećuje Varda.

Iz Agencije za zaštitu životne sredine poručuju da se „uvođenjem Ekosistemskog pristupa Barselonske Konvencije i usklađivanjem monitoring programa praćenja stanja morskog ekosistema sa istim i budućim zahtjevima Direktive o morskoj strategiji, očekuje sprovođenje detaljnijih analiza uzroka i pritisaka u odnosu na konstatovano stanje“.

Kada se mogu očekivati prva detaljnija istraživanja pritisaka kruzera na bogati i živopisni svijet Kotorskog zaliva, ostaje nejasno.

U fokusu reaktivne misije Uneskovog Međunarodnog savjeta za spomenike i spomenička područja (ICOMOS- International Council for Monuments and Sites), nakon posjete Kotoru u oktobru prošle godine, bila je pretjerana urbanizacija na području Kotorskog zaliva, a kruzeri su bili tema 2017. godine.

Imajući u vidu da nije samo kulturno-istorijsko već i prirodno područje Kotora pod zaštitom Uneska, kao i da postoje planovi da se određeni djelovi Zaliva zbog specifičnosti živog svijeta stave pod posebnu zaštitu, ICOMOS je u dokumentu pod nazivom „Venecijanska utvrđenja između 15. i 17. vijeka na području Italije, Hrvatske i Crne Gore“ eksplicitno kao prijetnju po zaštićeno područje Kotora naveo „veliki broj kruzera i teretnih brodova koji vrše pritisak“ na Kotor.

O kruzerima je prošle godine za njemački poslovni nedjeljnik Wirtschaftswoche (WiWo) govorila i Mechtild Rössler, direktorka Uneska za kulturnu baštinu. Ona je u članku „Ko plaća za rast kruzing turizma” ocijenila da „kruzeri nanose štetu mjestima na kojima zarađuju”. Zbog toga, kako prenosi hrvatski Index.hr, Rössler apeluje na vlasnike kruzera da više ulože u očuvanje kulturne baštine, ali i da razviju brodove koji će manje zagađivati okolinu.

(Ne)zaštićena morska područja

Crna Gora, Bosna i Hercegovina, San Marino i Vatikan jedine su mediteranske zemlja koje nemaju zaštićeno nijedno morsko područje. Crna Gora je, doduše, jedina od njih deklarisana kao „ekološka država”. To će morati da se promijeni do zatvaranja poglavlja 27 o ekologiji, jer je, prema evropskim propisima, nužno da se zaštiti barem jedno morsko područje.

Zaštićena područja u moru su širom svijeta decenijama prepoznata kao najefikasniji način za očuvanje morskog ekosistema i sprovođenje svih mjera zaštite i konzervacije mora i obale, kaže Dušan Varda.

Agencija za zaštitu prirode i životne sredine uradila je studiju izvodljivosti za buduće morsko zaštićeno područje Platamuni 2015. godine, u kojoj se napominje da je prošle godine pokrenut projekat „Promocija upravljanja zaštićenim područjima kroz integrisanu zaštitu morskih i obalnih ekosistema u obalnom području Crne Gore“, u vrijednosti od milion i 799 hiljada dolara, koji će se finansirati iz Globalnog fonda za životnu sredinu (GEF), a realizovaće ga UNEP-ova kancelarija (program Ujedinjenih nacija za životnu sredinu), iz Beča u saradnji sa crnogorskim Ministarstvom održivog razvoja i turizma.

„Već deceniju traju pripreme. Sudeći prema planovima, možemo se nadati da ćemo za manje od tri godine imati proglašena prva zaštićena područja u moru u okolini ostrva Katič ispred Petrovca, od Platamuna prema zalivu Trašte, u okolini Ratca i Žukotrlice, Starog Ulcinja i Valdanosa“, napominje Varda.

„Princeze“ od 330 metara

Najveći kruzeri koji su do sada uplovili u Kotorski zaliv su mega kruzer „Majestic Princess“, dug 330 i visok 68 metara, od 144.216 bruto registarskih tona, te „Royal Princess“, koji je dug 330 i visok 66 metara, sa 141.000 bruto registarskih tona. Broj putnika koji mogu da se ukrcaju na ove kruzere prelazi tri i po hiljade, svaki prima i po nešto manje od hiljadu i po članova posade.

Boravak ovih velikih brodova u Kotorskom zalivu nije vezan samo za turističku sezonu. Prema podacima Luke Kotor, u ovaj grad stižu tokom cijele godine. Kruzeri Regina della Pace, Artemis i Athena tradicionalno otvaraju sezonu kruzing turizma, budući da su prvi koji pristižu u Kotorski zaliv (od 2013. do danas u kotorsku luku uplovljavaju između 1. i 4. januara), ali je najčešće i zatvaraju, i to uglavnom 31. decembra.

Samo četiri pritužbe

Uprkos četvorocifrenom broju kruzera koji su uplovili u Kotorski zaliv, Uprava pomorske sigurnosti je dobila svega četiri pritužbe prilikom prolazaka i boravka. Prvenstveno su se odnosile na eventualna zagađenja mora koja su kruzeri počinili.

Iako brojni snimci na društvenim mrežama svjedoče o zamućenom moru oko kruzera, naši sagovornici vjeruju da nije riječ o opasnom otpadu, već najvjerovatnije o mulju koji su podigli motori ili povlačenje sidara po dnu, jer kruzeri uglavnom dolaze iz zemalja u kojima su takve stvari nedopustive.

Međutim, podatke o tome koliko je kruzera do sada iz bilo kog razloga sankcionisano za vrijeme boravka u Bokokotorskom zalivu i šta su najčešći povodi za određivanje sankcija, od Lučke kapetanije Kotor, Inspekcije sigurnosti i bezbjednosti Kotor, i Ministarstva saobraćaja i pomorstva, nismo dobili ni nakon duže od pola godine.

Matija OTAŠEVIĆ

As funds granted by the World Bank remain unused the government is unmoved by some 7.5 million tonnes of hazardous waste that loom over the country. On the other hand the authorities' response to environmental incidents is merely symbolic whereas ordinary people have to bear the brunt of enormous environmental damage. The Brussels administration is not delighted with the Montenegrin government’s request to postpone tackling ecological problems caused by the aluminum smelter (KAP) for year 2030.

”There’s no future here in the next thousand or so years. The pollution is unbelievable. We can’t drink water here, we can’t grow plants, the underground water courses have been poisoned for 45 years” says Drago Terzic, a resident of Srpska, a village in close proximity to the aluminum plant and its red mud pools. The place is also plagued by piles of garbage and abandoned houses only 9km away from the centre of Montenegro's capital Podgorica. The Aluminum facility was once the prime giant of socialist industry. Its heyday passed long time ago but the consequences remain and are highly visible.

The Bauxite tailings are easily accessible. There is neither security around the place nor warning signs. Two red mud ponds which store around 7.5 million tonnes of hazardous waste are situated next to the smelter. One pond has non-permeable bottom while the other has no leaking barrier thus heavy metals and carcinogens penetrate and poison the underground and the surface waters alike.

Drago Terzic and his first neighbour Boro Lazovic complain that whenever a stronger wind descends it lifts the dust from the ponds and carries it around. They shut themselves in their homes and wait for the wind to cease. They point out that a part of the Moraca River is totally contaminated and without fish.

Dijana Milev Cavor of Green Home NGO warns of the red mud dangers to the environment. Green Home conducted a research on Lake Skadar and its pollution in 2012. The main source of contamination is KAP. The research further states that KAP has generated some 325 thousand tonnes of solid waste which is labeled as hazardous due to high concentration of fluorides, nickel, chromium, copper, cadmium, zinc, arsenic, mercury, cyanide... which have penetrated the soil and underground water courses.

The bauxite residue in its dry form can become airborne by wind and spread over large areas. It can pose a threat to arable land and to human health.

Moreover the Centre for Eco-toxicological Research (CETI) has warned for years about soil and underground water pollution around KAP. The Montenegrin Investigative Reporting Centre's (CIN-CG) findings prove once more that the authorities’ response has been inadequate.

The World Bank granted a loan of €50 million five years ago to solve the problem of KAP’s bauxite tailings and solid waste. However, the project is stuck from the very beginning.

Montenegro’s request to postpone implementation of the EU ecological standards for 11 years is something unheard of so far- Gallop

The deadline for issuing Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control (IPPC) permit to KAP smelter expired on 1 Jan 2018. IPCC permits are one of the conditions for Montenegro-EU accession talks as thereby industrial facilities prove that they adhere to the best techniques of pollution prevention and control.

The Montenegrin authorities are totally unprepared for the said criteria hence they keep trying to obtain concessions from the Brussels administration and push the deadline all the way up to 2030. In the meantime the IPCC implementation has been formally halted under excuse of unresolved property disputes between KAP’s bankruptcy administration and the new Niksic-based owner Uniprom LLC.

The Brussels administration replied our inquiry via Delegation of the EU to Montenegro saying that Montenegro could not change rules and policies of the EU. The European Commission said that Montenegro’s request to postpone the implementation of the IPCC Directive would require “a detailed elaboration before the EU reaches decision (by consensus of all member states)”. Until then Montenegro is expected to comply with and implement the current regulation including the aforesaid directive. “The European Union does acknowledge that Montenegro plans to adopt certain implementation plans in 2019 which are related to the said directive. That is a prerequisite to continue business in the interim periods” says Brussels.

The Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism (MORT) told CIN-CG that it requested an interim period in regard to implementation of the IPPC Directive on industrial emissions. MORT cites the examples of other candidate states which lodged similar requests during their accession talks.

An EU expert and an environmentalist of England-based Bankwatch Pippa Gallop says in the interview with CIN-CG that it is entirely unacceptable to postpone the directive implementation till 2030. The standards are relatively high hence no guarantee that Montenegro’s request will be granted.

“I know that Croatia requested to postpone the directive implementation for a couple of years but the Montenegrin request is something unheard of and I see no grounds for such a motion” says Gallop.

Speaking of the World Bank loan she says it’s surprising how little has been done to resolve the issue of the red mud ponds. The plans are frequently changed and the WB evades talking about it.

"On the other hand, the conditions to unlock the loan have not been met while the bank is in no hurry. However, for human and environmental reasons the present situation is unacceptable and we’ll keep pressing them about it” said Gallop

Pollution is "being investigated"

Montenegrin prosecutors in the meantime say they investigate last September and October incidents when the bauxite dust took off from the red mud ponds and contaminated the surrounding area. That was not the first time though. The Podgorica Prosecution Office confirmed to CIN-CG that Environmental Inspectorate and nearby residents lodged complaints “which are being investigated”.

Berane-based company Wag–Kolektor has been the owner of the red mud ponds since Feb 2016. Inspectors asked the company to install a system for sprinkling along the edge of the ponds since the area was not completely covered by irrigation system. The inspectors warned that the present provisions were insufficient to prevent emissions of red dust.

Sinisa Jevric, one of the founders of Wag–Kolektor, in the interview with CIN-CG states that all requests of the inspectorate will be fulfilled by the middle of the year.

On the other hand, the fines for non-compliance are rather jokes. Last October the aforesaid company was fined €300 while the owner nearly got away- he has to pay no more than €30.

The inspectors also investigate whether caustic soda leaked from the aluminum smelter into the Moraca River. However, it has been established that a certain amount of lye ended up in the smelter's sewage system. No good news arrive from there.

Any stronger earthquake could cause red mud to spill

Ana Misurovic, a former CETI executive and a toxicological expert, wrote in 2004 that people living around the aluminum smelter were risking their health by exposure to intoxicants in air, water and food...

The collapse of a dam on much larger bauxite tailings in northern Hungary 9 years ago caused the death of 9 persons while hundreds were injured and a large surrounding area was contaminated.

Misurovic in her interview with CIN-CG reckons that in case of a strong earthquake the red mud could spill out of the basins. She believes that no one has examined the potential threat so far.

Soil and underground waters around KAP were examined by CETI before. CIN-CG obtained CETI’s reports for 2016 and 2017 which stated that no improvement had been made. Physical and chemical analysis made in 2016 confirmed the presence of nitrates, zinc, cyanide, orthophosphate and ammonium above the red line levels in the underground water courses within the smelter's boundary.

CETI also analised the soil around KAP in those years and each report warn about increasing levels of chromium, nickel, fluorine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons...

Environmental Protection Agency came up with similar findings in 2017 and blamed the aluminum smelter for the pollution.

Fishy transactions with red mud basins

OZON NGO director Aleksandar Perovic finds the authorities’ silence on pollution unacceptable and “possibly fatal to the population around KAP smelter”. Perovic criticises the whole thing about the loan granted by the World Bank as nothing has changed in reality. He lists the red mud basins as another example of botched privatisation.

“It made no sense to separate the bauxite tailings, a notorious black spot, from KAP smelter and hand it over to someone else”. The first company which took over the red mud basins had plans to extract the material which could be used in road constructions. “Unfortunately, the investor could not obtain the permits and left. Then the place ended up, under murky circumstances, in the hands of a company which was without any experience in the aforesaid business” says Perovic.

He further claims that it’s a public secret that the only aim of the privatisation is to resell the bauxite tailings to the government so that it becomes a part of KAP again. Thus everyone with fingers in the pie will his handy commission. Perovic is adamant that “the company (Wag-Kolektor) is not capable, both financially and in terms of expertise, to operate the red mud basins”.

However, Wag-Kolektor told CIN-CG that they had plans to restart the red mud procession together with its German partner by the middle of this year. Jevric denied that he had intention to sell the ponds to anyone. Nonetheless he did confirm that he was summoned by a local prosecutor to give a statement about the red dust emission at the end of last year.

MORT- standards must be adhered to regardless of permits

In the 2017 review the government states that KAP’s technology is outdated and incapable of implementing the EU standards in less then 10 years.

“ The issue of KAP is a very complex one. It’s not only a question of environmental and security risks but it comes together with the current bankruptcy protocol, ownership over bauxite tailings so to meet all the criteria set forth by the World Bank...” is stated by MORT.

Polluters to be held accountable

Uniprom hasn’t replied CIN-CG questions on the company’s vision in regard to environmental issues caused by the smelter’s operations and whether and when the company will apply for intergrated permit.

The government recently drafted a bill on industrial emissions which will introduce a new rule- “the polluters shall pay”. The fines will range from €5,000 to €40,000 for legal entities if they operate without permits or if they fail to submit anual reports on the quality of soil, air, water, sea etc.

Maja BORIČIĆ

The World Health Organisation data show that 6 % of deaths in Podgorica, 12 % in Niksic and 22 % in Pljevlja are caused by air pollution. The authorities and polluters keep delaying actions which would help reverse the situation

At the end of January the alarm bells rang in Skopje due to dramatic air pollution which was 10 times more that allowed. The government prolonged school break, introduced free public transport and doubled parking fees so to discourage the use of vehicles. Furthermore the government recommended older people as well as those with chronic diseases not to go to work for a while.

However, the Montenegrin government did not bother itself with similar measures even though the air pollution in Podgorica was 18 days above the red line in the end of December. The alert in Pljevlja lasted 29 days in the same month. Furthermore, the Centre for Eco-Toxicological Research recorded in the end of November the greatest ever pollution in Plevlja- 23 times more than it is allowed.

The Government and the biggest polluters keep tossing responsibility to each other and always come up with new bureaucratic and other excuses so to evade strategic projects which would cut the air pollution. On the other hand the population’s health keeps deteriorating. Pljevlja is a city notorious for population exodus. CIN-CG & Monitor investigation points out to Podgorica and Niksic as seriously affected by air pollution.

The World Health Organization (WHO ) reports that 6 % of all deaths in Podgorica, 12 % in Niksic and 22 % in Pljevlja can be attributed to air pollution. The studies on these three towns point out to more than 250 premature deaths, 140 hospital admissions per year and a number of other health related issues due to exposure to particles which exceeds the WHO prescribed values- it is reported by the Institute of Public Health of Montenegro.

This institution states that the annual rate of premature mortality associated with exposure to particular pollutants in Montenegro is up to 60 times higher than the fatal road accidents.

In response to questions submitted by CIN-CG & Monitor, the Institute, cited details from The impact of air pollution on health in Montenegro, which was published in 2016 and compiled by WHO expert Dr. Michal Krzyzanowski, a visiting professor at Kings College in London.

High values of carcinogens benzo (a) pyrene in the PM 10 particles (diameter of less than 10 micrometers) exceed the boundaries of up to 15 times. This polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon contained in coal tar is listed in the first group of carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. It causes tumour of the ovary, lymph nodes, breasts, liver, digestive tract, lung, and leukemia.

Outdoors activities at your own risk

Record air pollution for years has ranked Pljevlja among the ten most polluted cities in Europe – according to WHO. The Institute of Public Health does not recommend outdoors activities there, especially when it comes to children and youth.

The Environmental Protection Agency in its response to CIN- CG & Monitor says that the air in Montenegro is primarily affected by solid fuels used for heating and nearly 200,000 registered motor vehicles with an average age of over 14 years. When it comes to heavy industry the main polluters are Plevlja Thermoelectric Plant, Pljevlja Coal Mine and Niksic Steel Plant (Toscelik).

"The air pollution problem exists in Tetovo, Prilep, Skopje, Zenica, Tuzla, Sarajevo, Uzice ...Thus when it comes to PM 10 and PM 2.5 particles Pljevlja have the same level as those cities. But, if we talk about heavy presence of other chemical elements - nitrogen, sulfur dioxide, thorium, uranium, and others then Pljevlja has outpaced all other cities by far" said Milorad Mitrovic, the executive of Breznica NGO.

He pointed out to the local health centre data released at the end of April last year. In just four months 35 women in Plevlja, aged between 35 and 50, were treated for breast cancer.

A few years ago the media published a sad story about 11 people in Pljevlja who were all family related. They all died of lungs cancer within a year. Dr Vesa Jecmenica (died in 2015) claimed in 2012 that a genetic mutation was in full swing in Pljevlja. Thus in addition to malignant diseases growth there was also a growth of congenital anomalies.

The Pljevlja Epidemiological Office reported 395 visits due to malignancy issues in 2017. The National Register of Malignant Neoplasms reported 175 newly registered cases of cancer in Pljevlja in 2013. There’s still no data for 2014.

Heating Plant, finally?

The latest government report boasts that “the government and its institutions are striving to improve the air quality in Montenegro, with special emphasis on Pljevlja“. The Environmental Protection Agency further elaborates the government efforts saying that they refer to construction of small power plants and heating system in Pljevlja. The authorities will also work to improve the air quality monitoring on the national level ...

The national power company (EPCG) announced the investment of €60 million in environmental protection, while the Pljevlja Coal Mine claims that it spends more than €10 million annually. The Agency states that a heating plant in Pljevlja would permanently solve the problems in the town center, provided that most homes are integrated in the heating network. This project would cost at least €20 million and has been talked about for years.

The mayor of Pljevlja, Mirko Djacic halted the heating plant tender in February last year, because the bids were declared invalid. Prior to the local elections in the spring of 2018, the municipal leaders and government officials were promising that pollution reduction would become tangible in the very same year. After they won the elections, the construction of the heating plant did not even begin. The contractor, Tim Company in Pljevlja, has not yet received the construction permit from the Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism (MORT).

“We expect MORT to issue the permit this week “ said Mervan Avdovic, the vice-chairman of Pljevlja’s City Council . He would not talk about deadlines for the project completion but he said that the construction would be swift.

Vaso Knezevic, a landscape architecture engineer and environmental activist in Pljevlja, explains that each polluter should be ordered certain things in order to help the environment. "The coal mine should reclaim the Jagnjilo Pit so to reduce the negative effects of the mining machinery. The dust from the open pit lands on the whole area... Then the thermoelectric power plant should install desulphurisation and slag removal filters…. The heating plant is perceived as the best solution and is spoken about for some 30 years, but we haven’t come to that in real terms yet" said Knezevic.

Mitrovic reminds that the authorities often stress the unfavorable climate and geographical position, because the town is surrounded by hills thus being deprived of air circulation.

“That is true, but the town is built in depression. Furthermore, over 120 million tonnes of material from the mine have been piled up on the hill. That disrupted the wind rose. There is no more north wind that used to clean the town’s air. The landfill of Culina Guka on the edge of the town prevents the air flow, while Velika Plijes and Mala Plijes landfills close the air flow on the town’s south. The coal mine changes the landscape and our living conditions. The abandoned open pit mines in Sumana and Borovici are filled with water and the surrounding landscape looks like Mars” says Mitrovic.

Running away as far as possible

The Coalition 27, which brings together the most important NGOs dealing with ecology, states that there are no strategies for air quality improvement in four municipalities, although the air pollution is on the rise. Implementation of the Pljevlja Strategy is still not satisfactory. There are no visible results yet and the level of pollution has remained the same as in the previous years.

Monstat- Statistical Office of Montenegro, records a negative migration balance for Pljevlja in the last decade. Pljevlja is number one in Montenegro when it comes to population exodus - the number of deaths exceeds the number of births by 144.

In the first week of February the Pljevlja City Council’s ruling majority rejected the proposal of the entire opposition to endorse emergency measures against pollution. The opposition asked the Council to press charges in court against the government for its deliberate obstruction of environmental protection plans. The opposition also wanted the EPCG power company and the Pljevlja Coal Mines to define the measures whereby they will tackle the overall pollution in accordance with the EU standards and recommendations.

Nonetheless the majority supported the “ongoing government efforts”.

Pollution and harmful effects

According to the Institute of Public Health, the so called rough PM10 particles increase the respiratory illnesses and mortality rates. They aggravate asthma, bronchitis and other similar diseases.

The EU regulations as well as Montenegrin tolerate an average PM10 daily value of 50 micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3) which must not be exceeded more than 35 days a year. Official statistics show that from 2011 to 2018 the excessive presence of those particles in Podgorica lasted from 64 to 89 days a year, in Niksic from 104 to 147, and in Pljevlja from 144 to 217 days.

The average annual concentration of PM 10 particles should not exceed the ceiling of 40 μg/ m3. However Podgorica is near the line each year at 37.38, and in 2015 it was 41.91 μg/m3.

The data for Niksic show 43 to 62, while in Pljevlja those values go up to a staggering 99.81 μg/m3 recorded in 2015.

An increase in the average annual value of the "fine" PM 2.5 particles (diameter less than 2.5 micrometres) was recorded in Niksic and Pljevlja. The red line value is 25 μg/m3. In Niksic it is often at the border value, while in Pljevlja the recording exceeds 40 micrograms every year which qualifies the city among the most polluted in Europe.

EPCG: Plans and predictions and more lip service

The Montenegrin Electricity Utility (EPCG) replied to CIN CG & Monitor that the company was doing its best. They state that in 2013/14., they implemented a project that stabilized the Maljevac Landfill boundary wall. Moreover the expropriation of the nearby land is in progress so to afford a buffer zone. The Maljevac reclaim project is worth €20 million and another €40 million have been assigned for fixing Block 1 of the Pljevlja Thermoelectric Plant.

The EPCG says it’s is keen to reduce the content of oxides, sulfur and nitrogen in flue gases, then to construct a wastewater treatment plant, a new system of dry transport of ash, slag and chemical gypsum, as well as to remove asbestos from the cooling tower.

The Coal Mine AD Pljevlja told CIN CG & Monitor that it regularly conducts controls of waste oils and lubricants. Moreover they spend €150,000 each summer for sprinkling dirt roads to keep the dust down.

In early 2018 the sewage sludge purifier was put in action for the Cehotina River water treatment near the open pit mine there. The investment amounted to €280,000.

“We regularly conduct checks. The total cost of testing the air and water in the last five years reached €104,000 “said the Coal Mine press service.

Predrag NIKOLIĆ

Dok novac odobren od Svjetske banke čeka, vlasti ne rješavaju problem 7,5 miliona tona opasnih materija, simbolično reaguju na ekološke incidente zbog kojih građani ispaštaju, a posljedice po životnu sredinu su nemjerljive. Brisel ne gleda blagonaklono na zahtjev crnogorskih vlasti da se rješavanje ekoloških problema KAP-a odloži za 11 godina

,,Ovdje jednostavno nema sreće sljedećih hiljadu i po godina. Toliko je zagađeno. Ne smijemo da pijemo vodu, ne možemo da sadimo, podzemni tokovi vode su zatrovani već 45 godina.”

Mještanin Srpske Drago Terzić, ovako slika život pored bazena crvenog mulja i u okolini Kombinata aluminijuma. Gomilom smeća i napuštenim kućama počinje deveti kilometar od centra Podgorice, putem do zetskih naselja u blizini nekadašnjeg giganta crnogorske industrije, koji je u socijalističko doba knjižio i do jedan odsto svjetske proizvodnje lakog metala, ne mareći za teške posljedice po okolinu. Takve proizvodnje odavno nema, ali se ekološka šteta nastavlja.

Bazenima crvenog mulja, neriješenim crnim ekološkim tačkama, može se prići bez problema, jer nema nikakvog obezbjeđenja tog prostora, kao ni stražara koji bi upozorio na opasnost. Na dvije lokacije neposredno uz KAP odloženo je oko sedam i po miliona tona opasne materije. Jedan bazen ima nepropusno dno, dok je drugi bez zaštite, te se zemljište i podzemne vode stalno zagađuju teškim metalima i kancerogenim česticama.

Terzić, stari ekološki aktivista, i njegov prvi komšija Boro Lazović kažu da, kad dune jači vjetar, sa bazena počinje da se diže prašina i nastaje haos. Zatvore se u kuće i čekaju da prođe. Uvjeravaju i da je dio Morače koji se nalazi u blizini KAP-a potpuno zatrovan, da uopšte nema ribe.

,,Taj ko kaže da je ova voda iz Morače i Skadarskog jezera dobra, radi protiv svoje familije i truje sopstveni narod znajući da je voda otrovna. To je pokušaj ubistva sa predumišljajem“, ističe Terzić.

Dijana Milev Čavor iz Green Home objašnjava da crveni mulj, kao nusproizvod prerade boksita i glavni materijal za elektrohemijsku proizvodnju aluminijuma, može da izazove ekološku katastrofu.

Prema istraživanju ,,Zagađenje Skadarskog jezera” koje je još 2012. godine uradio Green home najozbiljniji izvor zagađenja Skadarskog jezera su otpadne vode, koje nastaju u toku tehničko-tehnoloških procesa u Kombinatu aluminijuma Podgorica. Ove vode sadrže toksične i opasne materije.

U studiji piše da je, tokom više decenija rada KAP-a, stvoreno i oko 325 hiljada kubika čvrstog otpada, koji je deponovan na odlagalište i klasifikovan kao opasan, zbog sadržaja fluorida, nikla, hroma, bakra, kadmijuma, cinka, arsena, žive, cijanida...

„Nađene su značajne koncentracije opasnih i štetnih materija koje su prodrle u zemljište i podzemne vode“- piše u Studiji.

Prašina crvenog mulja, ako je suva, pojašnjava Milev Čavor, može vjetrom da se raznosi na veće udaljenosti, na obradivo zemljište i da ugrožava zdravlje stanovništva.

„Jedna od mjera za sprečavanje migracije ove prašine je redovno polivanje vodom bazena sa muljem. Ali to omogućava stvaranje procjednih tečnosti i njihovu penetraciju u zemljište i podzemne vode“, kaže ona.

I drugi, uključujući i Centar za ekotoksikološka ispitivanja (CETI) godinama upozoravaju na opasnost zagađenja podzemnih voda i zemljišta oko KAP-a, vlasti ne preduzimaju adekvatne mjere, pokazalo je istraživanje Centra za istraživačko novinarstvo Crne Gore (CIN-CG).

Uprkos zajmu od 50 miliona eura, koji je još prije pet godina odobrila Svjetska banka (CB), da se, između ostalog, riješi problem ovih bazena i deponije čvrstog otpada u okviru KAP-a, taj projekat je i dalje na samom početku.

Galop: Ovo još nijesam čula

I rok za izdavanje integrisane dozvole (IPPC) KAP-u istekao je 1. januara 2018. godine. Ove dozvole su uslov u pregovorima za ulazak Crne Gore u Evropsku uniju. IPPC je jedna od ključnih direktiva EU u oblasti zaštite životne sredine i njome je predviđeno da operateri industrijskih postrojenja moraju pokazati da sistemski primjenjuju najbolje dostupne tehnike radi sprečavanja i nadzora zagađenja.

Potpuno nespremni za to, umjesto konkretnih poteza, vlasti od Brisela pokušavaju da izmole novi rok – čak do 2030. godine. Postupak dobijanja, odnosno izdavanja integrisane dozvole u međuvremenu je i formalno prekinut, uz obrazloženje da postoje neriješeni imovinsko pravni odnosi između KAP-a u stečaju i sadašnjeg vlasnika nikšićkog Uniproma.

Crna Gora ne može uvoditi amandmane na pravila ili politiku Evropske unije (EU), remetiti njihovo funkcionisanje ili dovesti do neprikladnog narušavanja konkurencije, poručili su ovim povodom za CIN- CG iz Brisela, u odgovorima proslijeđenim posredstvom Delegacije Evropske komisije u Crnoj Gori.

Na pitanje šta misle o zahtjevu Crne Gore za odlaganje primjene Direktive, iz Evropske komisije su procijenili ,,da će biti potrebne dodatne detaljne informacije prije nego što EU zauzme stav o tome”.

,,EU podsjeća na svoj opšti pregovarački stav da su prelazne mjere izuzetne, vremenski i obimom ograničene, i praćene planom koji ima jasno definisane faze. Stoga, prelazni periodi nisu razmatrani u ovoj fazi, ali će biti dio pristupnog sporazuma, ako se slože sve države članice, uključujući i njihovo trajanje, a sve na bazi pouzdanih planova za usklađivanje", piše u odgovoru Evropske komisije za CIN-CG.

Do tada, kažu, očekuju da Crna Gora nastavi sa usklađivanjem i primjenom akata, uključujući i tu Direktivu.

“Evropska unija uzima u obzir da Crna Gora planira da u 2019.g. usvoji posebne planove primjene iz Direktive i podvlači da je to preduslov za dalji posao na prelaznim periodima”, dodaje se u odgovoru Brisela.

Iz Ministarstva održivog razvoja i turizma (MORT) za CIN-CG kažu da su, nakon što je otvoreno poglavlje 27, tražili prelazni period za primjenu IPPC direktive o industrijskim emisijama, te da su slične zahtjeve imale i ostale zemlje regiona u procesu pristupanja EU.

Ekspertkinja EU i ekološka aktivistkinja engleskog Bankwatch-a Pipa Galop je za CIN-CG ocijenila da je potpuno neprihvatljivo odugovlačenje do 2030. godine, da su standardi relativno strogi, te da je pitanje koliko će se to dozvoljavati Crnoj Gori.

“Znam da je Hrvatska tražila odlaganje Direktive na par godina, ali ovo je najduži period za koji sam čula, ne vidim razlog za to", navela je Galop.

Što se tiče zajma Svjetske banke, ona ocjenjuje kako je nevjerovatno koliko se malo radi na rješavanju problema bazena crvenog mulja, koliko se mijenjaju planovi, te koliko SB izbjegava da govori o tome.

"S druge strane vjerovatno još nijesu ispunjeni uslovi da se taj kredit oslobodi i koristi, a banka nije u žurbi, jer njima je svejedno kad će to biti, ali sa ljudskog i ekološkog aspekta to je apsolutno neprihvatljivo i mi ćemo ih pritiskati da se bave time", izjavila je Galop.

Trovanje ,,u izviđaju”

Crnogorsko tužilaštvo je, u međuvremenu, počelo da ispituje čija je krivica što se, prošle godine u septembru i oktobru, po ko zna koji put, podigla prašina sa bazena crvenog mulja i dodatno zagadila okolna naselja. Potvrđujući za CIN-CG, da su reagovali na prijavu Ekološke inspekcije i mještana Zete, rekli su da je formiran predmet u Osnovnom državnom tužilaštvu u Podgorici i da se ,,postupak nalazi u fazi izviđaja”.

Beranska firma Wag – Kolektor je od februara 2016. godine vlasnik bazena crvenog mulja. Tada ih je prodao DOO Politropus Alternative Tivat, koji je bazene ranije kupio od KAP-a. Inspekcija je tražila od beranskog preduzeća da se na kompletnom obodu bazena instaliraju funkcionalne prskalice za orošavanje bazena, jer sav prostor nije pokriven sistemom navodnjavanja.

„Da se izvrši bušenje i aktiviranje trećeg bunara za navodnjavanje plaža bazena, radi obezbjeđivanja dovoljne vlažnosti površine plaža u cilju sprečavanja emisije crvene prašine, jer količine vode iz dva postojeća bunara nijesu dovoljne“, navedeno je iz inspekcije.

Siniša Jevrić, jedan od osnivača firme Wag – Kolektor u razgovoru za CIN-CG tvrdi da će do polovine godine realizovati sve zahtjeve inspekcije, odnosno da planira da osposobi i treći bunar do maja ili juna.

Simbolične kazne nijesu dovoljan motiv za investiranje u zaštitu životne sredine. Inspekcija je do sada zbog neizvršavanja naloga, pored kazne od 7.500 eura, pred podgoričkim Sudom za prekršaje pokrenula postupak protiv beranske firme, u martu prošle godine. Sud je u oktobru izrekao kaznu preduzeću od 300 eura. Vlasnik je kažnjen ,,čitavih” 30 eura.

Inspekcija sada ispituje i da li se prije nekoliko dana živa soda izlila u Moraču iz KAP-a, a nedavno je utvrdila da se izvjesna količina lužine ulila u kanal otpadnih voda tog preduzeća. Sa ove neuralgične tačke po životnu sredinu, jednostavno nema dobrih vijesti.

Jači zemljotres mogao bi izazvati izlivanje mulja

Da život u naseljima oko KAP-a nema perspektivu, konstatovala je još 2004. godine vještak toksikološke struke i tadašnja direktorica CETI-a Ana Mišurović, ocjenjujući kvalitet zemljišta u naseljima u blizini bazena crvenog mulja. U njenom nalazu piše da supstance kojima su neprestano izloženi stanovnici naselja u okolini KAP-a mogu prouzrokovati veoma teška oboljenja, zavisno od ukupnog dnevnog unosa pojedinih toksikanata preko vazduha, vode, namirnica...

Kada je prije devet godina na sjeveru Mađarske popustila brana jednog, znatno većeg i aktivnog bazena sa crvenim muljem poginulo je devet osoba, povrijeđeno više stotina, a ogromno područje je zatrovano.

Mišurović je za CIN-CG ocijenila da i danas postoji mogućnost da se crveni mulj iz kruga KAP-a izlije iz bazena u slučaju jakog zemljotresa, ili ukoliko bi popustila konstrukcija.

“Unutra se nalazi alkalna sredina, zavisi u kojoj mjeri se ocijedila i da li se ocijedila. Mislim da ispitivanja o tome koliko bi to bilo opasno, niko ne obavlja,”, navela je ona.

Kvalitet zemljišta i podzemnih voda oko KAP-a CETI je ispitivao i kasnije. Izvještaji iz 2016. i 2017. godine, koje je dobio CIN-CG, govore da napretka nema.

„Prema rezultatima fizičko-hemijske analize, uzorak podzemne vode uzorkovan na lokaciji KAP-a u stečaju ne odgovara nijednoj od klasa Uredbe o klasifikaciji i kategorizaciji površinskih i podzemnih voda zbog povećane mutnoće, sadržaja suspendovanih materija, nitrita, cinka, cijanida, ortofosfata i amonijum jona“, piše u jednom od izvještaja CETI iz 2016.godine.

Samo u jednom dokumentu s kraja decembra 2017. godine, stoji da se podzemne vode mogu koristiti za piće nakon određene obrade. U ostalim mjesecima, ove podzemne vode ne odgovaraju nijednoj od klasa zbog povećane mutnoće i prisustva teških metala.

Tokom 2016. i 2017. CETI je više puta analizirao zemljišta oko KAP-a i u svakom izvještaju je utvrđeno da ne odgovara uslovima Pravilnika o dozvoljenim količinama opasnih i štetnih materija u zemljištu zbog povećanog sadržaja hroma, nikla, fluora, policikličnih aromatičnih ugljovodonika…

I u informaciji o stanju životne sredine za 2017. godinu koji je uradila Agencija za zaštitu životne sredine se, između ostalog, u ispitivanjima zemljišta u selu Srpska, koji se nalazi uz KAP, navodi da je povećan sadržaj pronađenih štetnih materija povezanih sa radom Kombinata.

Sumnje u česte transakcije sa bazenima

Direktor nevladine organizacije OZON Aleksandar Perović, ocjenjuje da je neprihvatljivo ćutanje institucija o problemu zagađenja ,,koji bi mogao biti poguban za stanovništvo koje živi u okolini KAP-a”.

„Okolnosti se vremenom samo komplikuju, u kontekstu promjena vlasništva, nejasne podjele nadležnosti u okviru samog KAP-a, odvajanja bazena crvenog mulja od industrijskog kompleksa, koji je takođe bio dio neuspješne privatizacije. Taoci su građani i to područje“, ocijenio je Perović, za CIN-CG.

Naglašavajući da su elaborati i studije kojim je trebalo da započne rješavanje ekološkog problema novcem Svjetske banke ostali samo mrtvo slovo na papiru, Perović ističe da su bazeni sa crvenim muljem još jedan primjer kako ne bi trebalo izvoditi privatizaciju.

„Nije bilo logično da se jedna istorijska crna tačka, kakvi su bazeni, odvoji od matičnog industrijskog kompleksa KAP-a i da se da u vlasništvo nekom drugom“, ocijenio je on.

Firma koja je prvobitno privatizovala bazene, prema njegovim riječima, imala je plan da taj materijal prerađuje u građevinske podloge, kako bi ga izvozila i upotrebljavala za izgradnju saobraćajnica i slično.

„Nažalost stvoren je ambijent da investitor nije mogao da pribavi potrebne saglasnosti i on je odustao. Pod sumnjivim okolnostima došlo je do transakcije da takav objekat završi u vlasništvu firme iz Berana koja se nikad nije bavila ovim poslovima, kao i nijedna druga u Crnoj Gori”, rekao je on.

Perović tvrdi da je javna tajna, da je jedini interes i motiv te privatizacije bio da se mulj opet preproda državi i da se u tom procesu svi ugrade, pa da opet bude dio KAP-a ili državna svojina.

„Ta firma nije sposobna ni finansijski, ni ekspertski da sanira bazene i upravlja njima“, kategoričan je Perović.

Iz WEG Kolektora su za CIN CG, međutim, rekli kako planiraju da do polovine ove godine opet pokrenu preradu crvenog mulja u konzorcijumu sa njemačkim partnerom.

Jevrić je, za CIN-CG, negirao da namjerava da ikome proda bazene, ali i potvrdio da ga je tužilaštvo zvalo da da izjavu oko podizanja crvene prašine krajem prošle godine.

,,To vam je isto kao kad se podigne prašina sa asfalta... Ovo što ja radim ide u prilog svima”, rekao je on, što je potpuno u skladu sa zaprijećenom kaznom od 30 eura.

MORT: Obaveze važe i bez dozvole

U Vladinoj informaciji iz 2017. godine piše da je tehnologija KAP-a zastarjela, te da neće biti u stanju da za period koji je kraći od deset godina u svojim proizvodnim procesima primijeni evropske standarde.

U MORT-u kažu da rade na specifičnom planu implementacije Direktive, koji je poslat na prevod, nakon čega će biti proslijeđen EK. Neposjedovanje integrisane dozvole, kako ističu, ni u jednom trenutku ne oslobađa operatera postrojenja od zahtjeva utvrđenih drugim propisima koji se odnose na zaštitu životne sredine.

,,Rješavanje pitanja remedijacije na dvije lokacije vezane za KAP je veoma kompleksno, ne samo zbog ekoloških i pitanja bezbjednosti i zaštite od rizika, već i zbog tekućeg stečajnog postupka koji se vodi nad KAP-om, vlasništva nad bazenima crvenog mulja, a sve u cilju zadovoljenja kriterijuma i procedura Svjetske banke...", piše u odgovoru MORT-a.

Jednom će zagađivać morati da plaća

Ekološka inspekcija je, u martu prošle godine, tražila pokretanje prekršajnog postupka protiv KAP-a u stečaju i stečajnog upravnika Veselina Perišića zbog nepribavljanja dozvole.

Sudovi su ih, međutim, pravosnažno oslobodili krivice, kako saznaje CIN CG, jer za to ne bi trebalo da odgovara stečajni upravnik, već sadašnji vlasnik KAP-a- nikšićka firma Uniprom Veselina Pejovića.

Iz Uniproma nijesu odgovorili na pitanja CIN CG-a šta rade i planiraju da urade da zaštite životnu sredinu od procesa koji se obavljaju u KAP-u i da li će i kada tražiti pribavljanje integrisane dozvole.

U Zakonu o integrisanom sprečavanju i kontroli zagađivanja životne sredine piše da se dozvola izdaje na određeno vrijeme, a najduže na deset godina. Propisane su i novčane kazne za rad bez dozvole Agencije i to od 5.000 do 15.000 eura za pravno i 500 do 1.000 eura za odgovorno lice.

Predviđena je i mogućnost izricanja zabrane obnavljanja djelatnosti od mjesec do godinu dana.

Vlada je nedavno utvrdila i novi predlog zakona o industrijskim emisijama, kojim se uvodi načelo „zagađivač plaća”. Predviđene su nešto veće novčane kazne od 5.000 do 40.000 eura za pravno lice, ako, između ostalog, počne s radom postrojenje bez dozvole, ako jednom godišnje ne bude dostavljalo rezultate mjerenja, ako organu uprave ne dostavlja podatke o rezultatima monitoringa emisija zemljišta, vazduha, vode, mora i ostalih segmenata životne sredine.

Maja BORIČIĆ

BANNED IN MONTENEGRO BUT BELOVED IN ALBANIA, TRADITIONAL "DALJANI”, OR FISH WEIRS, ARE BEING BLAMED FOR A DRAMATIC FALL IN FISH STOCKS IN LAKE SKADAR.

Dzelal Hodzic fondly remembers the biggest catch of his life.

“You could feel it by the noise,” said the veteran Montenegrin fisherman. “It was night, and they just said ‘lift!’ It took us from morning until the following night to get it out. We didn’t know what to do with that much fish.”

It was October 1971, and Hodzic – now head of the environmental group Green Step – and his colleagues had just landed 23 tonnes of fish in a single net, trapping them with a weir as the fish headed back to the Adriatic Sea from spawning in the fresh waters of river Bojana. They sent the catch north to be sold in Croatia’s medieval town of Dubrovnik, when Croatia and Montenegro were both part of socialist Yugoslavia.

Such stories have long since become legend in the communities that live off this lake, which straddles the border of Montenegro and Albania.

Dams, construction, pollution and over-fishing have cut the lake’s fish populations dramatically.

The sturgeon has been gone for decades, while the endangered European eel, the leaping mullet, thinlip mullet and twait shad are all at risk.

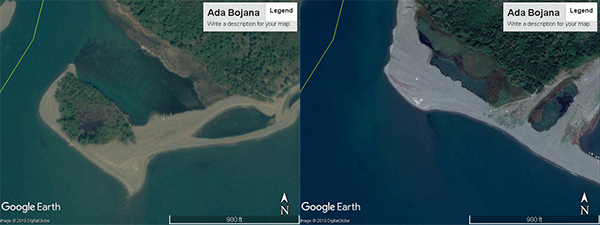

The use of fish weirs is banned in Montenegro, but the traps are permitted by Albania, where they are known as ‘daljani’ and have a history stretching back for centuries.

But while authorities in Albania say the daljani are used in line with the law and cannot be blamed for falling stocks, fishermen in Montenegro say they are devastating the lake.

“The Albanians have cut off the lake; a fly can’t get past,” said Marko Masanovic, a member of the Professional Fishermen’s Association of Ulcinj, a coastal town in southern Montenegro near the Albanian border.

“We have nothing this year: prawns, leerfish… nothing,” he told the Centre for Investigative Reporting of Montenegro and Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, CIN-CG/BIRN.

“Before, you could fish with rods. Now, even a net doesn’t help.”

Centuries of tradition

Daljani are barricades made of metal or wooden canes placed at the mouth of a channel between a lake and the sea, channeling the fish as they try to return to the sea from the lake into a trap, from where they are lifted out in a net known in Albanian as a ‘kalimera’.

The traps have been used for centuries in Albania, their V-shaped nets catching whole shoals of migrating fish.

In the late eighties and early nineties, they were run by the state, but fell increasingly under the control of local Albanian families during a period of intense turmoil in the country towards the close of the 20th century.

They are now in the hands of concessionaires, who operate the weirs under state supervision.

Albanian authorities insist there are strict rules on when and how much the daljani can be used. But a number of industry insiders told BIRN there was considerable room for abuse.

In August 2018, when under the law passage through the channel must be free, CIN-CG/BIRN reporters observed a daljani with its net hoisted above the water, as would be expected during the fishing ban season. But a few days later, CIN-CG/BIRN reporters observed that the net was below water, suggesting it was in use.

Two unidentified men on a boat threatened CIN-CG/BIRN reporters trying to shoot pictures, saying the site was private property and filming was not allowed.

Albania’s Deputy Minister of Agriculture, Roland Kristo, said the daljani were used in line with the law. “And the law is very clear,” he told CIN-CG/BIRN.

Under the law, the daljani on the River Bojana, which flows from Lake Skadar to the Adriatic Sea, are open between March 15 and August 31, and closed for the rest of the year.

The concession is granted for a period of two years and is monitored by Albania’s Organisation for Management and Maintenance of Skadar Lake.

“The daljana are not a novelty, this is a tradition,” said the head of the organisation, Arijan Cinari.

“They are open for half a year, and then closed. In these six months when they are closed, there are days when they should be open,” he told CIN-CG/BIRN. “We control these days. We do not do it ‘by chance’ or to favour someone. We just want to support the reproduction of fish in Skadar Lake.”

“I don’t think there any such ‘heroes’ who would risk their licence for a day or two, or even a week of poaching.”

Ichthyologist Danilo Mrdak of the University of Montenegro, however, said such rules would do little to help fish stocks. The daljani are designed to catch the fish precisely when it is trying to migrate, he said.

“There is no other reason why thinlip mullet, or the leaping mullet, is not entering and is not present in the amounts the fishermen are used to in Lake Skadar,” he said.

“There is no other reason for the lack of twait shad. Since democracy arrived in Albania, our fishermen have been having constant problems, because we have a constant decline in catches,” Mrdak told CIN-CG/BIRN.

“Only in those years when the water level went above the grids did something manage to get through…. But we are at God’s mercy.

No precise data on decline

Precise catch statistics over the past 40 years are not available.

With the demise of the socially-owned company Industriaimport, which managed fishing on the lake, and the closure of the ‘Ribarstvo’ factory in Rijeka Crnojevica, the only reliable register of fish catches from Lake Skadar were lost.

Records from 1947 to 1976, considered relatively reliable, show a considerable decline every year.

According to one report, if mullet was caught at a rate of 250 tonnes 30 years ago, today the yearly catch is roughly 5-6 tonnes, with the decline attributed to a range of factors.

“I remember when I started out, I caught ten times more than I catch now,” said Nikola Vujanovic, a fisherman from Rijeka Crnojevica, a village on the shores of Lake Skadar.

The daljani “stop everything that moves from either side of the river,” he said.

Only the joint efforts of the Montenegrin and Albanian governments can address the issue.

“It is true that this problem has been around for a long time and that we are trying to solve it,” said Slavica Pavlovic, head of the Fishing Directorate at the Montenegrin Ministry of Agriculture.

In July 2018, the two countries agreed to enhance the work of a joint Water Management Commission on Lake Skadar and the Bojana, the Drim and the Moraca rivers.

Podgorica also plans to commission a study of the effects of the dams on the River Bojana on fish populations as part of a conservation project being implemented by the German development agency GIZ.

“It is evident that there is a decline in the leaping mullet and twait shad populations,” Pavlovic told CIN-CG/BIRN. “We need to obtain precise data in order to prepare a plan of lake management.”

“Though freshwater fishing remains a national level issue, if the issue is a cross-border one, it still has to be regulated by certain agreements and clear rules so that no country suffers due to the negative decisions of the other.”

‘We do not allow it to migrate and leave’

Included in 2010 on a ‘red list’ of threatened species compiled by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the eel is of particular concern. Fishing data show it is at a historic low and the European Union has recommended constant monitoring.

Mrdak, the Montenegrin ichthyologist, said it was vital to have a joint effort to protect the eel.

“When it comes in February, March and April as spawn, it can enter Bojana and our system is filled, but the problem is that the ell is not allowed to go back to the sea” he said. “We prevent 40 percent of ells to return and spawn.”

“There is more of ell along Europe’s coastline while the Atlantic coast abounds with it. This little bit that we are preventing is just a ‘drop in the ocean’,” Mrdak told CIN-CG/BIRN. “But it is not right to reap the benefits of the good conduct on the Atlantic coast, and for us not to bother.”

But in Albania, Kristo, the deputy agriculture minister, said falling eel populations was hardly unique to Lake Skadar.

“The eel is endangered worldwide; the reason is hard to find,” he said.

Kristo argued that it was in no one’s interest to illegally catch eels given that the Montenegrin and Albanian markets are small and the catch cannot be exported to the EU since the bloc bans the purchase of eels outside its borders.

“The fact is that the drop in eel numbers is not only the case here,” he said. Montenegro, on the other hand, allows trawling for eel, which Albania has banned, Kristo added.

Albanian ecologist Dajana Beko said that eels were endangered by pollution, poaching and climate change. Asked about the daljani, she replied:

“Dam management, legal or not, greatly affects the number and type of fish. If it is managed well it affects the fish, if not, it endangers fish and life in Lake Skadar.”

A MONEY-SPINNER FOR CENTURIES

Journalist and publicist Mustafa Canka says the daljani on the River Bojana have long been coveted as a lucrative source of revenue.

“If you are aware that this is an area where you can continuously fish, that there is constant migration of fish, then you know the value of this,” he said.

“You can see in the cadastral register of Skadar dating back to 1416 that there is a record of daljani. The hunting spots are recorded in the cadastral register of Skadar County. It is written in there precisely who this belongs to. You can lease it and there was an annual fee for it, and how much the state earns.”